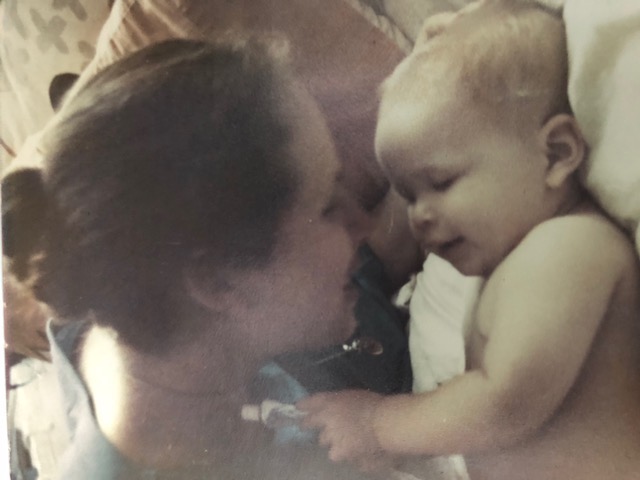

My daughter Nori with her son Alex on his birth day. Nori at 4 months with me.

The most complex of all relationships is noted one day a year on Mother’s Day. In looking up its history, something stood out—a requirement by Anna Jarvis, the day’s originator, that “Mother’s should be a singular possessive for each family to honor its own mother, not a plural possessive commemorating all mothers in the world.”:

As a daughter and stepdaughter, mother and stepmother, and grandmother, I return today to Anna’s original non-commercialized intent. I was interested in culling from my neighbors and friends, a sense of their family food history through childhood recipes. This “simple” subject multiplied into many—homemaking, siblings, family celebrations, and in some cases deep struggle. The fulcrum of all stories was the mother. Mine is too, as I navigated two intensely meaningful relationships, each quite different; and in my mother’s case challenging enough to compel an acceptance of inconsistency and evolution. My mother has never been my true north; this was my stepmother Margie's role—one she took up joyfully. But my mother’s own fragility has led me to an awareness that we all have lives that began and will extend well beyond our time as mothers and that nurturing can be found in many places.

My mother and me at the beach, our favorite outing. Margie and me at work together.

“Lost really has two disparate meanings. Losing things is about the familiar falling away, getting lost is about the unfamiliar appearing.”

Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

Being compelled to look within and without for nurturing, meant a habit of extending myself more widely and more hopefully into the world—be it neighborhood, the common history of friendship, or the glancing intimacies of community.

Drive-by Affirmation

A bit west of us, someone writes single sentence affirmations on a large chalkboard. I now look for this sign as I drive along Woodbury Road. Most memorable was, “You are seen;” so similar to the Zulu greeting, Sawubona,meaning, “I see you” and by extension, “I see your humanity. I see your dignity.”

Is it possible that an entire culture can embrace what we understand as the deepest form of nurturing—of being seen and therefore understood?

I See You: a collection of mother/daughter portraits of friends and neighbors. Each mother gazes directly at her daughter.

- I see you: Jo LaVonne Ewing and her mother Nell Brown Smith Chism, top left

- I see you: Trish Pengra and her mother Rose Majewski Farrow, top right

- I see you: Hope Tschopik Schneider and her mother Marion Hutchinson Tschopik, bottom right

- I see you: Doris Hausmann and her mother Hilda Hausmann, bottom left

Neighborhood Comfort

Trish lives across the street in a craftsman house that extends its greeting through a wide porch and at times, the sound of her playing the piano. After a harried day of moving into our home over a year ago, she arrived on our doorstep with a lasagna and cookies in hand. The next day, without my usual hesitation, I asked to use her dryer, soon carrying a basket of wet clothes across the street. Somehow, I knew I could ask for help.

Our kitchen window overlooking Jo's house.

Our next-door neighbor Jo’s kitchen window and back deck align with ours allowing the pleasure of casual connection. Although she must have endured more than her share of house construction noise and filth, she never complained. Well before our move in date—impatient to feel a sense of belonging—I placed a teapot on the counter by the window. She came by to let me know how happy she was to see this sign of life—as it meant the house was becoming a home.

The Connection of Common History

Barbara and I were two social orphans brought together through the intercession of Miss Rosen, our eighth-grade Home Room teacher at Bancroft Junior High School. I wonder if this teacher has any idea about how she changed the course of our lives. We now tell the story as family lore about our first conversation—ending with the discovery that we both loved to make art. This toe-hold of interest led to the building of a common history; almost family and more than family; Barbara is my dearest friend.

Peggy, an acquaintance within Pasadena's busy community of non-profits became something much more so after a walk taken together through our neighborhood. We found uncommon parallels in our personal histories, leaving us both stunned and connected. We speak and feel in a shorthand that comes through the familiarity of our common history—mothers who struggled with depression, fathers absent at times due to work in the foreign service, stepmothers named Margie.

From Rose's Homemaking Notebook, a collection of recipes, practical hints, and ephemera.

Marriages are Made in Kitchens, from the This n' That section of Rose's Homemaking Notebook. Trish's mother and father came from disconnected and at times neglectful families. Her father described his greatest accomplishment as creating "a happy family" of eight with his wife Rose.

From Jo's mother Nell's recipe for Apple Pie. Jo's family is from Kentucky, land of excellent sweets. (Pickle relish is a common savory ingredient.)

The Security of the Familiar

This week, I include family recipes from my friends and neighbors in their original form—a scrap of paper, the ubiquitous index card, and three ring notebook paper. Our mothers’ recipes assume knowledge that comes from learning side-by-side with them. The directions are brief and only make sense if knowing family context, history, and flavors. They are loved for more reasons than just taste.

Rose’s Sugared Crunch, Honey Crisp Bars, Crispy Peanut Squares

Nell’s Angel Biscuits and One Crust Apple Pie with Rich Topping

Barbara’s Whipped Cream Pound Cake

“My mother and her youngest sister would get together to bake around Christmas time. They watched the sales for butter and sugar and confered about how many batches to make. They made ten types of cookies and shared them out. When my aunt went back to work, my mom and I continued to bake together. I would take a day off of work, as we baked all day. When I bake now, I do so, to remember those days with my mom.”

Trish Pengra

“One thing that we have for Thanksgiving or Christmas or sometimes both is my mom’s apple pie—a kind of Dutch apple with butter, brown sugar and flour that is crumbled over the top. My son makes it now and my nephew loves to cook”

Jo LaVonne Ewing

And to end; it is definitely time for a poem.

Nurture

From a documentary on marsupials I learn

that a pillowcase makes a fine

substitute pouch for an orphaned kangaroo.

I am drawn to such dramas of animal rescue.

They are warm in the throat. I suffer, the critic proclaims,

from an overabundance of maternal genes.

Bring me your fallen fledgling, your bummer lamb,

lead the abused, the starvelings, into my barn.

Advise the hunted deer to leap into my corn.

And had there been a wild child—

filthy and fierce as a ferret, he is called

in one nineteenth-century account—

a wild child to love, it is safe to assume,

given my fireside inked with paw prints,

there would have been room.

Think of the language we two, same and not-same,

might have constructed from sign,

scratch, grimace, grunt, vowel:

Laughter our first noun, and our long verb, howl.

By Maxine Kumin