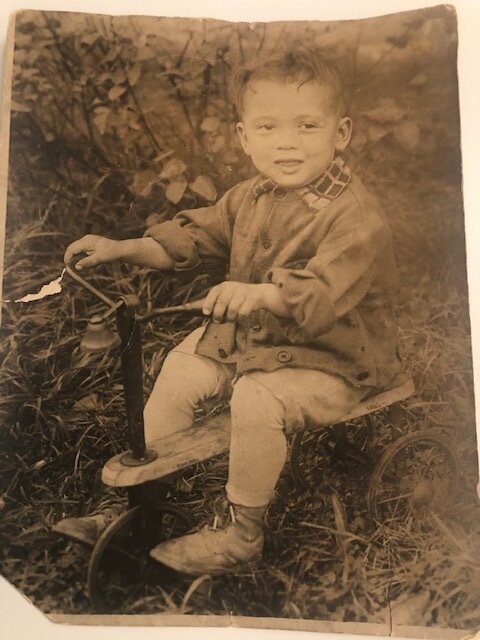

A Library circa 1950, My father at 2, Minh Phan and other chef buddies at porridge & puffs pre-COVID-19

My father grew up in the height of the Depression on the northwest side of Chicago in a Polish/Jewish enclave. At the end of his life, he began telling the stories of his youth and admitted to the depth of poverty he experienced. Called Peewee because of his small size, he remembers working at ten as a delivery boy for a local butcher. During one such delivery, he lost an order and was made to forfeit his wages until the loss was reimbursed. His family depended on his meager contributions and so, even at the end of a brilliantly successful life, he continued to feel shame. He also remembered two uplifting constants in his life that form the core of today’s writing: his frequent, almost daily visits to the neighborhood library and the delicious, nourishing meals shared by a neighbor when his family moved to the small town of Lyons, Michigan after his father secured a job there.

Libraries, in my mind, are the quintessential exemplars of a civic asset. They are the “clean, well-lighted places” that welcome all and form through their equity and aesthetic a sense of values writ concrete.

Because they are places for reading, research, and contemplation they can be respite to the intensity of a city’s psychic and sensory overload. (This of course, in the time before COVID-19.) Love of libraries is demonstrated over and over again. In my city of Pasadena, a parcel tax was passed by an easy 79.9 percent margin in 1999 to restore the Library budget to its pre-recession level. In 2011, a gutted Los Angeles Library budget was restored by a charter amendment supported by more than 63 percent of voters.

“All the things that are wrong in the world seem conquered by a library’s simple unspoken promise: Here I am, please tell me your story; here is my story, please listen.”

― Susan Orlean, The Library Book.

In this time of COVID-19, the small, neighborhood café and restaurant have an elevated role as similarly democratized community spaces that promise to prevail as such, even as our libraries, recreation centers, and cultural institutions begin to experiment with re-opening. They provide a needed break from our adventures in home cooking as well as personally curated selections of groceries and provisions. Through the simple act of feeding us, listening to us, and responding to us, they offer some semblance of our pre-COVID-19 communal life.

At every visit, we see the owners of the cafés and restaurants make it their business to welcome their customers and check in about their needs and desires.

Julie and Minh at the front door of their restaurants, every day.

They are pivoting on a daily basis, responding to complex, rigorous and changing health department requirements while remaining deeply committed to creating an experience of aesthetic and sensory nurturing without the bells and whistles of a wrap-around dining environment.

How do they achieve this seemingly incongruous magic trick of creating community and connection in a time of profound isolation?

I spoke to three food professionals, all small-business owners whose core strengths lie in considering and honoring the communities they support—their customers, their staff, and their suppliers--while committing to business practices based on ethical choices, no matter how challenging: Julie Campoy of Julienne’s, Minh Phan of porridge & puffs, and Onil Chibas of Onil Chibas Events Deluxe 1717.

“For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

--H. L. Mencken

There has been a great deal written about the punishing work cultures of restaurants and in many cases unfair labor practices, particularly for servers who often earn well below minimum wage when tips are designed to complete rather than supplement fair compensation. In smaller businesses, owners are often on similar footing as their staff, and in some cases are taking little or no salary as an extended stopgap measure.

Minh describes looking at her family’s personal finances as a way of reverse engineering the scope and scale of her restaurant’s life during the shutdown.

Some are looking at the virus as an extreme wake-up call, likening it as Julie described to “my time when I was diagnosed with breast cancer. It required enormous internal reserves, an ability to pivot, and a reminder that I just had to keep on walking.” She has been able to maintain a full- and part-time team of 50 (down from 65) and is committed to maintaining her staff, several of whom have been at Julienne’s for over 20 years.

Onil, a former manager at Disney Animation, began problem solving with an extensive personal review of what is possible and what he enjoys most about his work in food. “Although I loved many aspects of owning a restaurant, for me it was like a hamster on a wheel. Catering fits my love of project work with a beginning, middle and end, but now events like the 350-person gala is gone. And as I look to the future, do I really want to be schlepping those “cambro” boxes up another flight of stairs? So I was left with a weekly meal service as a sort of catering and restaurant experience combined, which allows me frequent contact with my customer-friends, consistent work for my small team, and a rational workload.”

Onil with chef and friend, Masako Yatabe Thomsen in Deluxe 1717, October 2019.

A Slight Digression

The average salary of wait staff in Copenhagen, a city with one of the highest costs of living in Europe, is nearly $2,000 per month--slightly higher than similar wages in Los Angeles. However--and this is a big however--the Danish government covers healthcare and includes significant housing subsidies (about 43% in Copenhagen), meaning a huge differential in the security and lifestyle of their workers.

Nourishment is a Form of Activism

The Protest Box from porridge & puffs

Minh’s customers are encouraged to purchase prix fixe meals as a form of giving back. For every [Jonathan] Gold Set Meal purchased, another is donated to a first responder. The Protest Meal Box ranges from free to full price, depending on ability to pay, and was created to support those actively protesting racism. Minh’s provisions are as unique as her food: makrut lemon jams, prickly-ash oil, sesame oil, and bulk grains, walnuts, and raisins from small farms. (Minh’s connection with local farmers is a part of her food-making heritage, as her first venue was a pop-up at the Hollywood Farmers’ Market.) She maintains a “strong team,” all of whom have adjusted without complaint: three chefs, including herself, and a front-of-house person. “The model is, you pay attention. You change on a dime. If the weather is hot, people want provisions. Fifty percent of our orders were cancelled during the curfew. We didn’t charge our customers; instead we created family meals and gave them to our neighbors, many of whom are really struggling.”

Julie with long-time Julienne chef Marcelline Dominguez in the days of hugging.

Julienne’s counter and to-go service was 60 percent of its revenues, which expanded overnight to 100 percent. Nearly every person on her team has transitioned to a new role: head waiter to head greeter, kitchen prep to grocery prep. Despite the herculean work behind the scenes, Julie’s brilliance is her sense of calm and welcome. She is as serene as a swan while paddling mightily underwater. She instituted “hazard pay” and every-other-week Friday Food Day, when all team members, including furloughed workers, are encouraged to take home produce, eggs, tortillas, cheeses. She too is listening to her customers.

“That’s how you are a good merchant, by asking your customers directly, what do you need? I can get that. I can do that.”

Along with an expanded number of Julienne-prepared standbys, there are shelves stocked--aesthetically--with sugar, flour, yeast, and even toilet paper.

A produce box filled with vegetables and fruits exemplifies her ability to transform a challenge into an asset. “A customer’s son sold produce to high-end restaurants, and suddenly there was no market. The next day, I asked him to put together these beautiful boxes that are for sale here.”

From Here On?

Libraries offer lessons here, as the advent of the computer was thought to be the death of them. Instead, they are proving to be as nimble as these much smaller businesses and have in fact recalibrated and celebrated some of their inherent strengths: community connection, a culture of service, access to content and technology.

Julie, Minh, and Onil are all considering their futures, and all are thoughtful enough to understand that this intensive and extended “moment in time” will have lasting impact on them.

Julie is clear; “I am really investing in creating an experience that is gracious and nurturing for now.” For her, that means baby steps toward thoughtful additions to service that are safe while maintaining the well-loved Julienne environment of aesthetics and pleasure. Very soon, Julienne’s will be providing an expresso bar and pastries in the morning for customers to pick up and take to socially distanced tables outside. Hours will be extended to take advantage of the “pink” of the lengthening days with a wine service.

Brandon, a greeter, Julienne style.

Onil sees the weekly meals as continuing even when he reopens Deluxe 1717. “My feeling with this whole thing is, we can’t be victims, otherwise you start feeling that it is something done to you. I want to approach this as a new venture. I really dove in and considered everything—how we would present the menu, involving other chefs and catering staff, supporting them and my customers.”

In what at first would seem counterintuitive during a time of daily upheaval, Minh decided that everyone still working would receive raises, saying “The most essential workers are often the most disadvantaged.” She is also a realist, understanding that the rock-and-hard-place for her is a commitment to fair wages while living through a recession’s depressed market and prices.

Are Restaurants the New Nonprofits?

There are so many examples of owners providing free food for their communities and initiating funds for unemployed workers. And, of course, there is World Central Kitchen’s José Andrés, who has been hiring laid-off restaurant workers to provide meals for the expanding numbers of unemployed. He is the impetus for the FEMA Empowering Essentials Delivery Act, which if passed, will not only provide FEMA funds for local and state governments to partner with restaurants and nonprofit groups to feed all those in need during COVID-19, but expands the understanding of need from short-term emergency fixes to ongoing support.

On a much larger scale, the pandemic has recalibrated our understanding of restaurants as essential services. Julie, Minh, and Onil were wholly aware of their potential to turn challenge and nourishment into a form of grace well before the pandemic.

Earlier days: Minh foraging at the late, great Muir Ranch. The beautiful poultry and mushroom porridge at p&p.

Work among all its abstracts, is actually intimacy, the place where the self meets the world.

Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Words David Whyte

To conclude, three recipes featuring the beautiful food of Julienne, Minh, and Onil.

All are condiments and add-ins designed to wake up everyday dishes: Crème Anglais, Minh’s Geranium Pickled Baby Onions, and Red Onion Jam.

For those of you have time to go deeper during this time of seclusion, some suggested reading:

The Library Book by Susan Orleans

To the Stars Through Difficulties by Romalyn Tilghman

My Restaurant Was My Life for 20 Years. Does the World Need It Anymore? by Gabrielle Hamilton

Shades of L.A.: Pictures from Ethnic Family Albums Edited by Kathy Kobayashi and Carolyn Kozo Cole

On a personal note by Julie Campoy