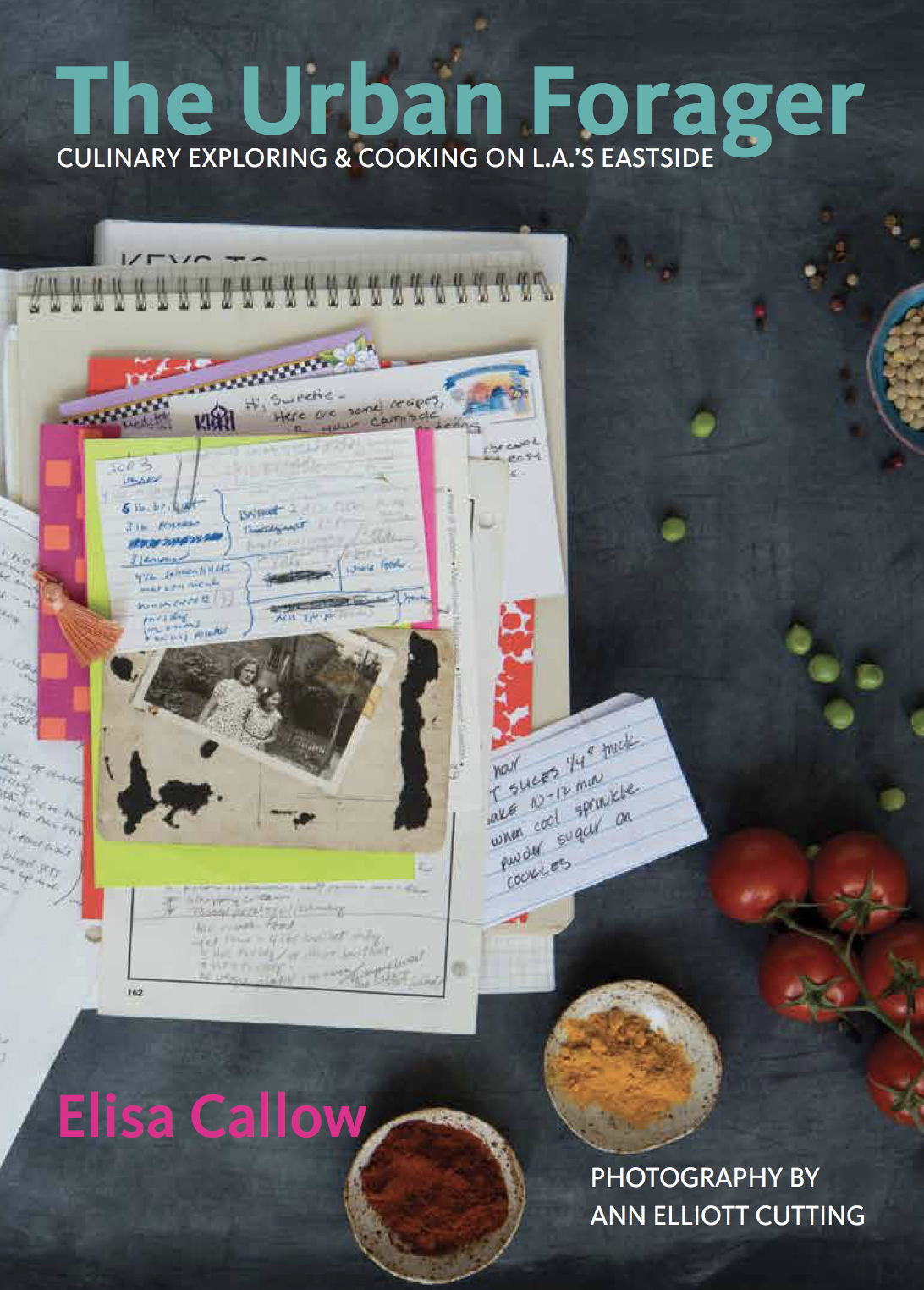

Two “safe” shopping adventures: Highland Park Farmers’ Market For those of you newly venturing out to open air markets, this one is a good bridge to the larger markets. It is one “lane” of fresh produce vendors, carefully monitored to assure safety, and never very crowded. Cookbook Market - A small and beautifully curated collection of small farm based produce, dairy, grains, oils, and vinegars. The Highland Park location is large enough to allow three shoppers at a time. All is carefully monitored for health safety.

And further afield: Bloom Ranch of Acton —Peach season is coming and nothing feels more relaxing than a visit to the open space of a happy farm. A small store sells fresh produce, eggs, and other goodies. Call ahead for peaches, as these are some of the best you will ever taste.

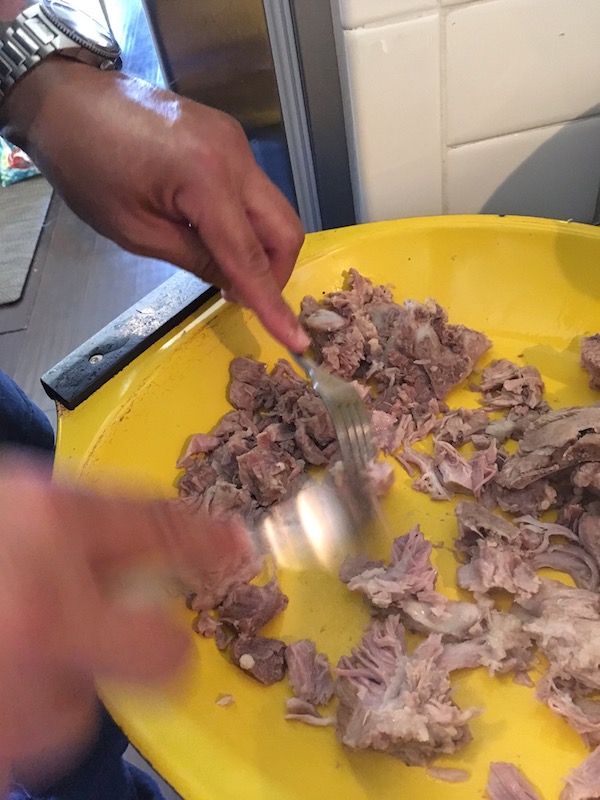

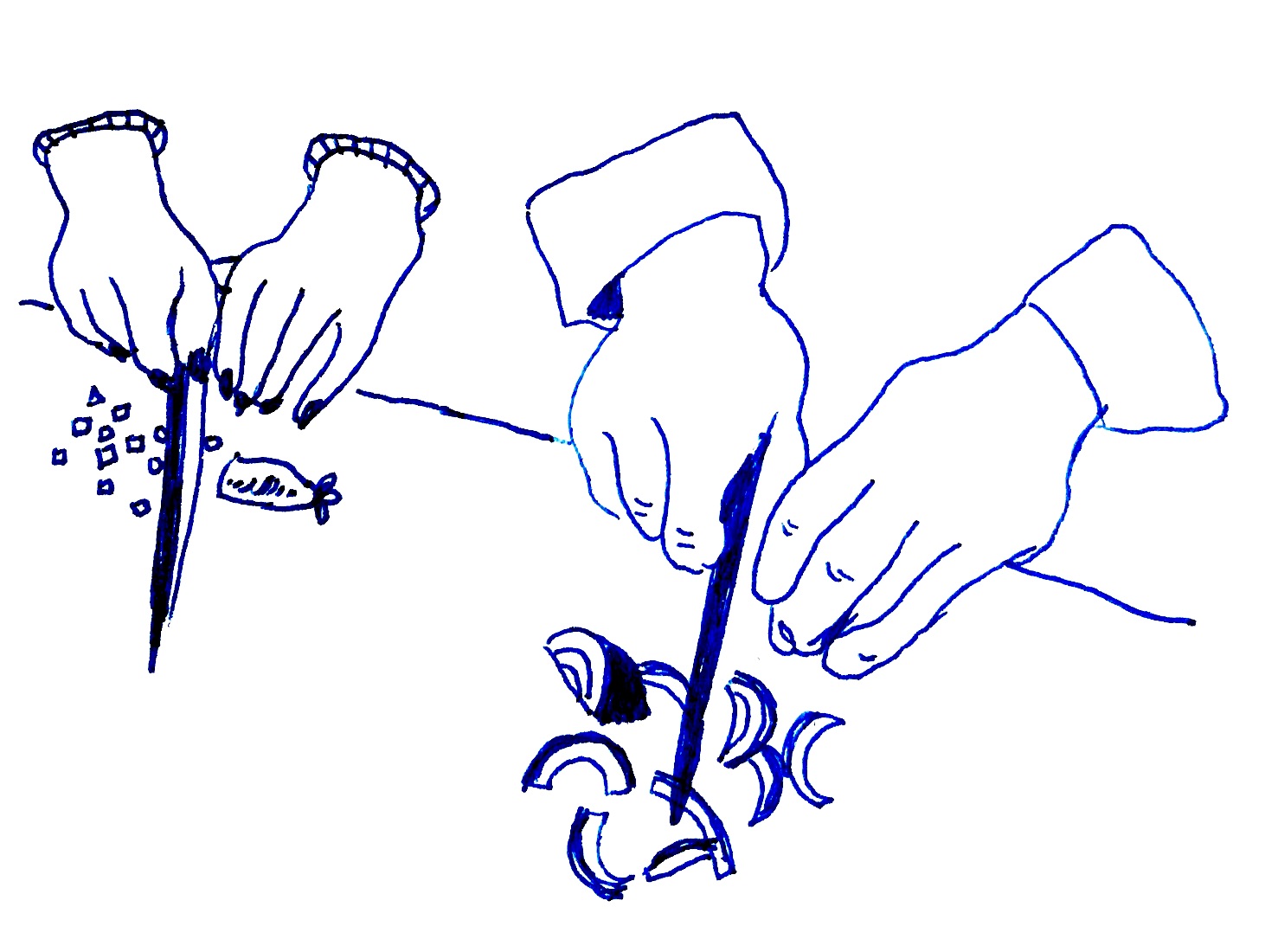

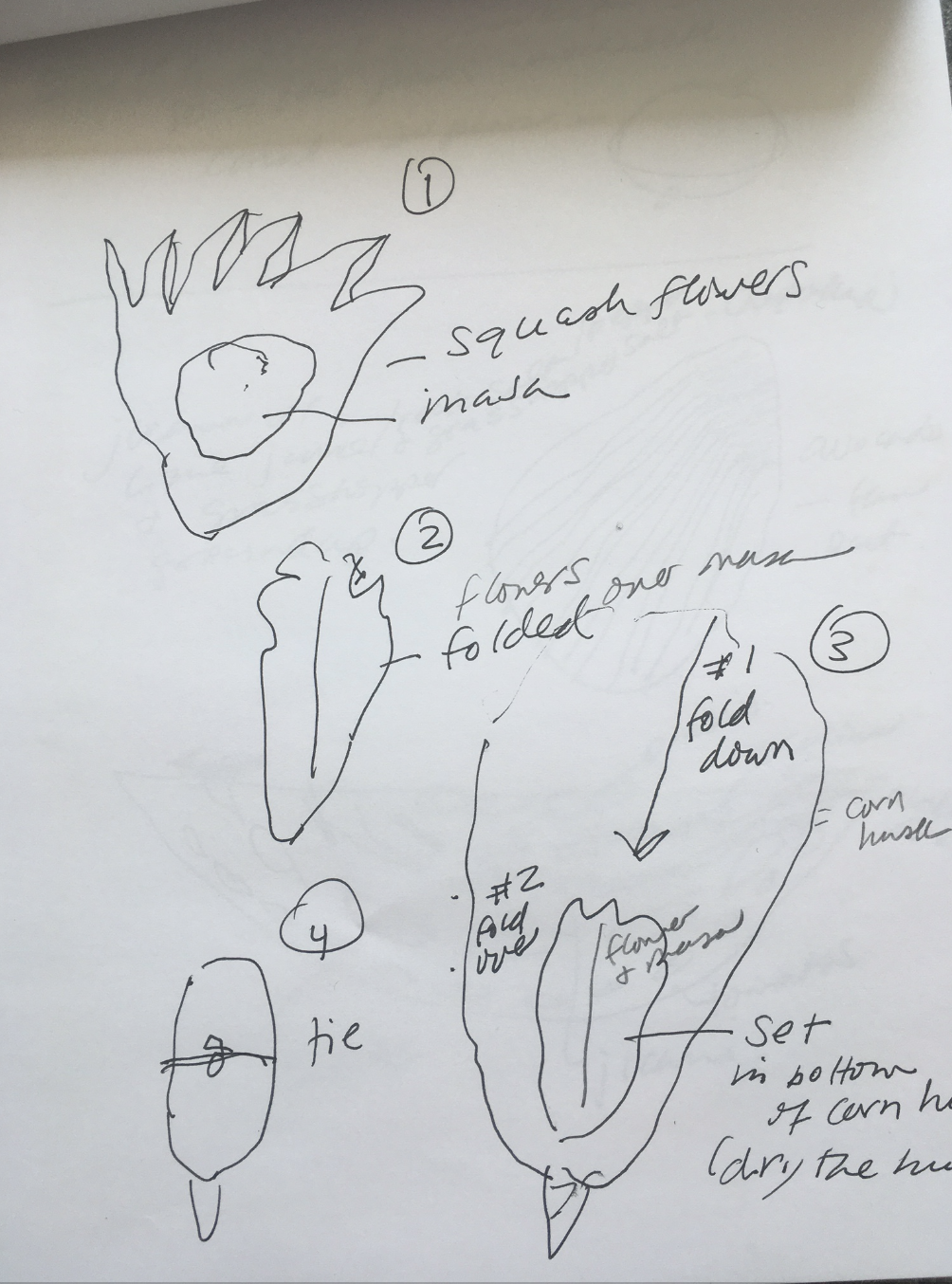

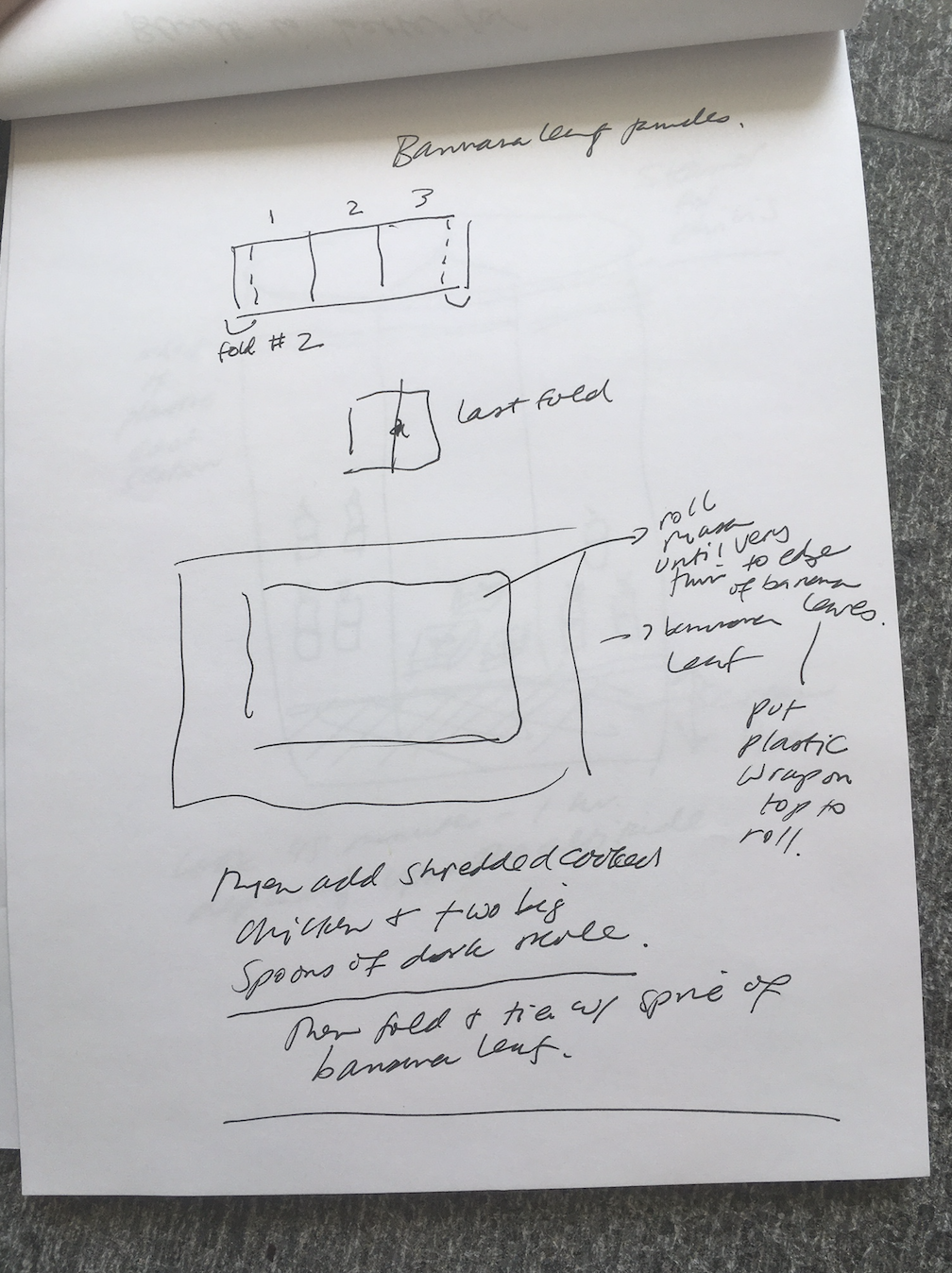

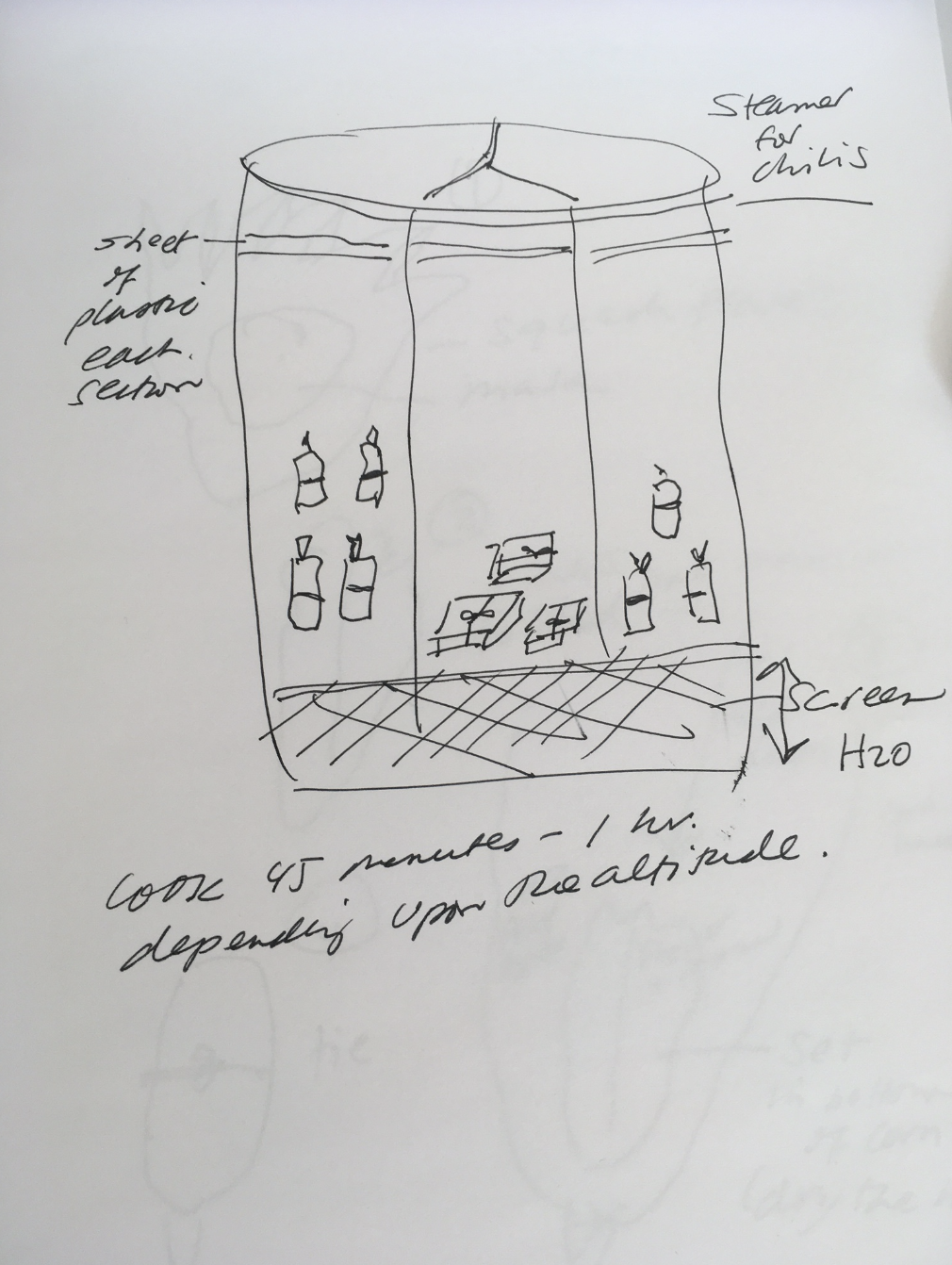

Recipes for “Pods”

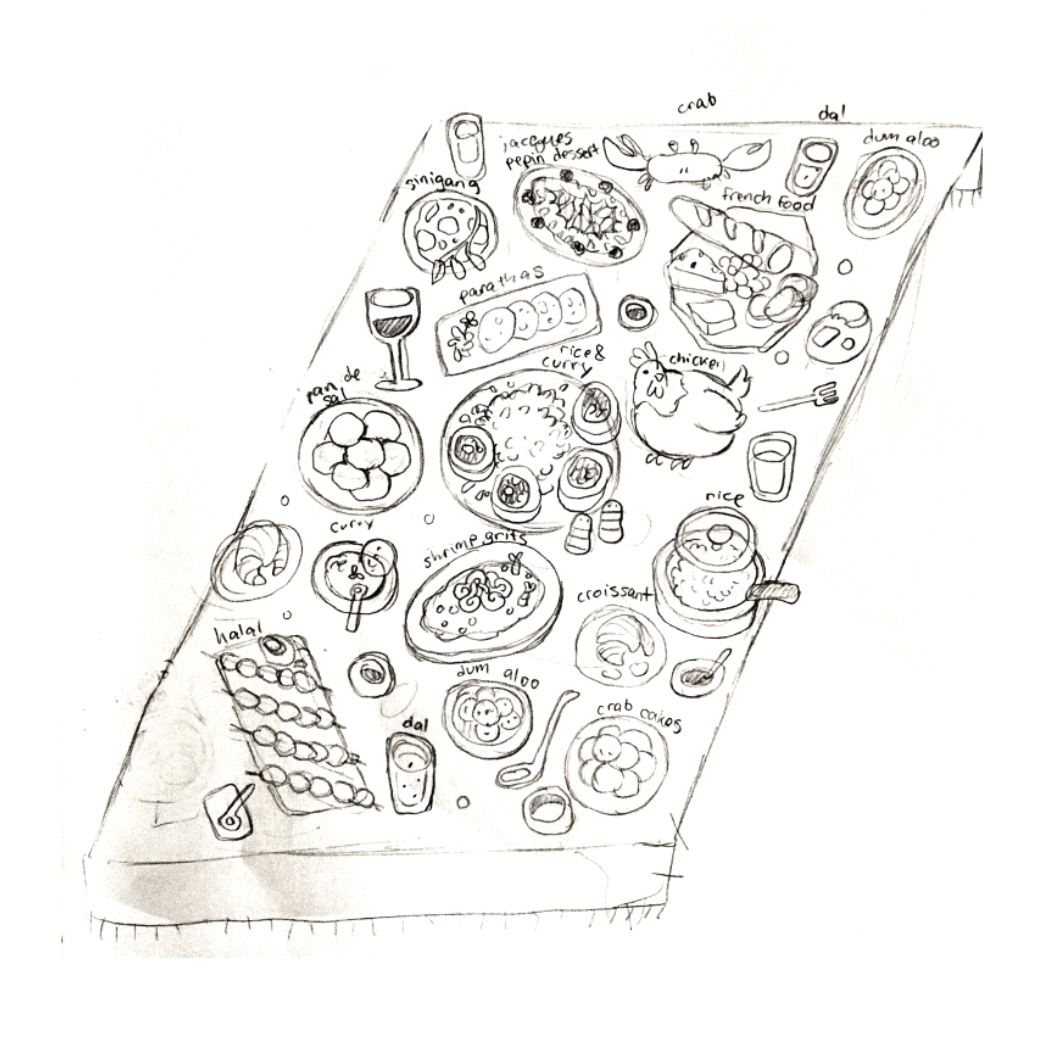

Marionne’s Cucumber Gazpacho, Summertime is Here: Fried Green Tomatoes with Basil Mayonnaise, and Campsite Pan Fried Layered Toast —a breakfast treat.

And three poems for our time:

Pandemania

By Daniel Halpern, Poetry Foundation, March 2013

There are fewer introductions

In plague years,

Hands held back, jocularity

No longer bellicose,

Even among men.

Breathing’s generally wary,

Labored, as they say, when

The end is at hand.

But this is the everyday intake

Of the imperceptible life force,

Willed now, slow —

Well, just cautious

In inhabited air.

As for ongoing dialogue,

No longer an exuberant plosive

To make a point,

But a new squirreling of air space,

A new sense of boundary.

Genghis Khan said the hand

Is the first thing one man gives

To another. Not in this war.

A gesture of limited distance

Now suffices, a nod,

A minor smile or a hand

Slightly raised,

Not in search of its counterpart,

Just a warning within

The acknowledgment to stand back.

Each beautiful stranger a barbarian

Breathing on the other side of the gate.

The End of Poetry

Ada Limón, Together in a Sudden Strangeness, 2020

Enough of osseous and chickadee and sunflower

and snowshoes, maple and seeds, samara and shoot, enough chiaroscuro, enough of thus and prophecy

and the stoic farmer and faith and our father and tis

of thee, enough of bosom and bud, skin and god

not forgetting and star bodies and frozen birds,

enough of the will to go on and not go on or how

a certain light does a certain thing, enough

of the kneeling and the rising and the looking

inward and the looking up, enough of the gun,

the drama, and the acquaintance’s suicide, the long-lost

letter on the dresser, enough of the longing and

the ego and the obliteration of ego, enough

of the mother and the child and the father and the child

and enough of the pointing to the world, weary

and desperate, enough of the brutal and the border,

enough of can you see me, can you hear me, enough

I am human, enough I am alone and I am desperate,

enough of the animal saving me, enough of the high

water, enough sorrow, enough of the air and its ease,

I am asking you to touch me.

Snow Day

By Billy Collins from Sailing Around the Room, 2001

Today we woke up to a revolution of snow,

its white flag waving over everything,

the landscape vanished,

not a single mouse to punctuate the blankness,

and beyond these windows

the government buildings smothered,

schools and libraries buried, the post office lost

under the noiseless drift,

the paths of trains softly blocked,

the world fallen under this falling.

In a while, I will put on some boots

and step out like someone walking in water,

and the dog will porpoise through the drifts,

and I will shake a laden branch

sending a cold shower down on us both.

But for now I am a willing prisoner in this house,

a sympathizer with the anarchic cause of snow.

I will make a pot of tea

and listen to the plastic radio on the counter,

as glad as anyone to hear the news

that the Kiddie Corner School is closed,

the Ding-Dong School, closed.

the All Aboard Children’s School, closed,

the Hi-Ho Nursery School, closed,

along with—some will be delighted to hear—

the Toadstool School, the Little School,

Little Sparrows Nursery School,

Little Stars Pre-School, Peas-and-Carrots Day School

the Tom Thumb Child Center, all closed,

and—clap your hands—the Peanuts Play School.

So this is where the children hide all day,

These are the nests where they letter and draw,

where they put on their bright miniature jackets,

all darting and climbing and sliding,

all but the few girls whispering by the fence.

And now I am listening hard

in the grandiose silence of the snow,

trying to hear what those three girls are plotting,

what riot is afoot,

which small queen is about to be brought down.

Til Next Time. Stay healthy in heart, mind, and soul.